Python Programming: Dictionaries

Learning Objectives

After this lesson, you will be able to:

- Perform common dictionary actions.

- Build more complex dictionaries.

Kicking Off Unit 3

In Unit 2, we ended by changing what our movie app printed depending on the value of a variable.

Unit 3 is about objects in programming.

- Objects are different kinds of things variables can hold.

- Objects help give our programs more structure and functionality.

- You already have one object down! Lists are an object with built-in functionality like

append()andpop().

In Unit 3, we’re going to add many more objects. By the end, your movie app will have the same functionality, but it will be structured in a totally different way.

Ready? Let’s go!

Introducing Dictionaries

Think about dictionaries — they’re filled with words and definitions that are paired together.

Programming has a dictionary object just like this!

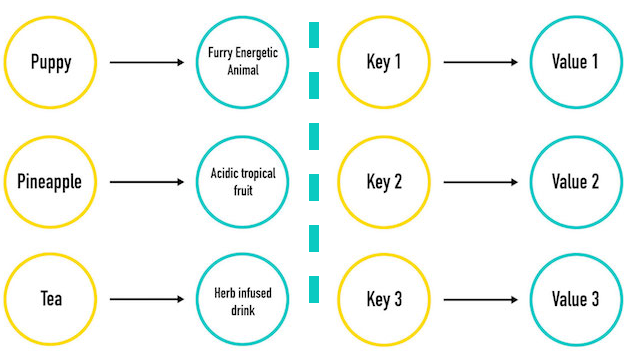

- Dictionaries hold keys (words) and values (the definitions).

- In a real dictionary, you can look up a word and find the definition. In a Python dictionary, you can look up a key and find the value.

Introducing Dictionaries

Declaring a Dictionary

Dictionaries in programming are made of key-value pairs.

# Here's the syntax:

name_of_dictionary = {"Key1": "Value", "Key2": "Value", "Key3": "Value"}

print(name_of_dictionary[key_to_look_up])

# Prints the value

# And in action...

my_dictionary = {"Puppy": "Furry, energetic animal", "Pineapple": "Acidic tropical fruit", "Tea": "Herb-infused drink"}

print(my_dictionary)

# Prints the whole dictionary

print(my_dictionary["Puppy"])

# => Prints Puppy's value: "Furry, energetic animal"We Do: Dictionaries and Quick Tips

The order of keys you see printed may differ from how you entered them. That’s fine!

You can’t have the same key twice. Imagine having two “puppies” in a real dictionary! If you try, the last value will be the one that’s kept.

What’s more, printing a key that doesn’t exist gives an error.

Let’s create a dictionary together.

We Do: Dictionary Syntax

What if a value changes? We can reassign a key’s value: my_dictionary["Puppy"] = "Cheerful".

What if we have new things to add? It’s the same syntax as changing the value, just with a new key: my_dictionary["Yoga"] = "Peaceful".

- Changing values is case sensitive — be careful not to add a new key!

Quick Review: Dictionaries

We can:

- Make a dictionary.

- Print a dictionary.

- Print one key’s value.

- Change a key’s value.

Here’s a best practice: Declare your dictionary across multiple lines for readability. Which is better?

# This works but is not proper style.

my_dictionary = {"Puppy": "Furry, energetic animal", "Pineapple": "Acidic tropical fruit", "Tea": "Herb-infused drink"}

# Do this instead!

my_dictionary = {

"Puppy": "Furry, energetic animal",

"Pineapple": "Acidic tropical fruit",

"Tea": "Herb-infused drink"

}Discussion: Collection Identification Practice

What are a and b below?:

# What object is this?

collection_1 = [3, 5, 7, "nine"]

# What object is this?

collection_2 = {"three": 3, "five": 5, 9: "nine"}Looping Through Dictionaries

We can print a dictionary with print(my_dictionary), but, like a list, we can also loop through the items with a for loop:

Partner Exercise: Dictionary Practice

You know the drill: Grab a partner and pick a driver!

Create a new local file, dictionary_practice.py. Write a script that declares a dictionary called my_name.

- Add a key for each letter in your name with a value of how many times that letter appears.

As an example, here is the dictionary you’d make for "Callee":

Write a loop that prints the dictionary, but formatted.

Bonus (if you have time): If it’s only one time, instead print The letter l appears in my name once. If it’s only two times, instead print The letter l appears in my name twice.

Partner Exercise: Most Popular Word

With the same partner, switch who’s driving.

Write a function, mostPopularWord(), that takes a list of strings and returns the string that appears the most.

For example:

Hints:

- Create a dictionary with words as keys and the count as the values.

- Check if a key already exists with

if "key_to_check" in my_dictionary:.

Other Values

We’re almost there! Let’s make this more complex.

In a list or a dictionary, anything can be a value. - This is a good reason to split dictionary declarations over multiple lines!

Open this repl.it in a new window so you can see it all (the button in the top-right corner).

Summary and Q&A

Dictionaries:

- Are another kind of collection, instead of a list.

- Use keys to access values, not indices!

- Should be used instead of lists when:

- You don’t care about the order of the items.

- You’d prefer more meaningful keys than just index numbers.

my_dictionary = {

"Puppy": "Furry, energetic animal",

"Pineapple": "Acidic tropical fruit",

"Tea": "Herb-infused drink"

}You Do: Reverse Lookup

Finding the value from a key is easy: my_dictionary[key]. But, what if you only have the value and want to find the key?

You task is to write a function, reverse_lookup(), that takes a dictionary and a value and returns the corresponding key.

For example: