You can not select more than 25 topics

Topics must start with a letter or number, can include dashes ('-') and can be up to 35 characters long.

964 lines

30 KiB

964 lines

30 KiB

##  {.separator}

|

|

|

|

<h1>Python Programming: Objects and Classes</h1>

|

|

|

|

|

|

<!--

|

|

|

|

## Overview

|

|

This lesson walks through creating classes in Python. The lesson starts with We Dos for creating a class and instantiating objects from that class. It's followed by a We Do for class and instance variables. It ends with a few partner exercises, then a series of Knowledge Checks.

|

|

|

|

## Learning Objectives

|

|

In this lesson, students will:

|

|

|

|

- Define a class.

|

|

- Instantiate an object from a class.

|

|

- Create classes with class variables.

|

|

|

|

|

|

## Duration

|

|

50 MINUTES

|

|

|

|

## Suggested Agenda

|

|

|

|

| Time | Activity |

|

|

| --- | --- |

|

|

| 0:00 - 0:03 | Welcome |

|

|

| 0:03 - 0:10 | Class Overview |

|

|

| 0:10 - 0:25 | Creating Classes |

|

|

| 0:25 - 0:30 | Class Variables |

|

|

| 0:30 - 0:47 | Exercises |

|

|

| 0:47 - 0:50 | Summary |

|

|

|

|

## In Class: Materials

|

|

- Projector

|

|

- Internet connection

|

|

- Python 3

|

|

-->

|

|

|

|

---

|

|

|

|

## Learning Objectives

|

|

|

|

*After this lesson, you will be able to…*

|

|

|

|

- Define a class.

|

|

- Instantiate an object from a class.

|

|

- Create classes with default instance variables.

|

|

|

|

---

|

|

|

|

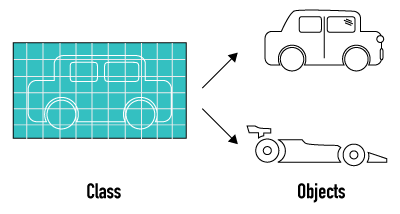

## Blueprints

|

|

|

|

All cars have things that make them a `Car`. Although the details might be different, every type of car has the same basics — it's off the same blueprint, with the same properties and methods.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- Property: A shape (could be hatchback or sedan).

|

|

- Property: A color (could be red, black, blue, or silver).

|

|

- Property: Seats (could be between 2 and 5).

|

|

- Method: Can drive.

|

|

- Method: Can park.

|

|

|

|

<aside class="notes">

|

|

|

|

**Talking Points:**

|

|

|

|

- When we make a car, we can vary the values of these properties. Some cars have economy engines, some have performance engines. Some have four doors, others have two. However, they are all types of `Car`s.

|

|

|

|

|

|

**Teaching Tips:**

|

|

|

|

- Point out the small "c" versus the big "C"!

|

|

- Encourage students to think of other commonalities of cars — get them thinking about an archetypal car.

|

|

|

|

|

|

</aside>

|

|

|

|

---

|

|

|

|

## Introduction: Objects and Classes

|

|

|

|

These properties and behaviors can be thought of as variables and functions.

|

|

|

|

`Car` blueprint:

|

|

|

|

- Properties (variables): `shape`, `color`, `seats`

|

|

- Methods (functions): `drive()` and `park()`

|

|

|

|

An actual car might have:

|

|

|

|

```python

|

|

# **Properties - Variables**:

|

|

- shape = "hatchback"

|

|

- color = "red", "black", "blue", or "silver"

|

|

- seats = 2

|

|

|

|

# **Methods - Functions:**

|

|

- drive()

|

|

- park()

|

|

- reverse()

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

**Discussion:** What might a blueprint for a chair look like?

|

|

|

|

<aside class="notes">

|

|

|

|

**Teaching Tips:**

|

|

|

|

- Give more examples on the board, both real-world and what students have seen.

|

|

- Get students to where they are able to define the concept of a class. Can they come up with examples, like the chair? (Feel free to change the chair to something else!)

|

|

|

|

**Talking Points:**

|

|

|

|

- Every day, we interact with objects like chairs, beverages, cars, other people, etc. These objects have properties that define them and behaviors we can execute to interact with them.

|

|

|

|

</aside>

|

|

|

|

---

|

|

|

|

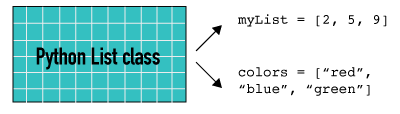

## Discussion: Python Classes

|

|

|

|

In Python, the concept of blueprints and objects is common. A **class** is the blueprint for an **object**. Everything you declare in Python is an object, and it has a class.

|

|

|

|

Consider the `List` class — every list you make has the same basic concept.

|

|

|

|

Variables:

|

|

|

|

- Elements: What's in the list! E.g., `my_list = [element1, element2, element3]`.

|

|

|

|

Methods that all lists have:

|

|

|

|

- `my_list.pop()`, `my_list.append()`, `my.list.insert(index)`

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

What behaviors and properties do you think are in the `Dictionary` class? The `Set` class?

|

|

|

|

|

|

<aside class="notes">

|

|

|

|

**Teaching Tips:**

|

|

|

|

- This is a tough slide, so spend a few minutes to make sure students get it.

|

|

- Have a discussion! Write on the board and have students brainstorm what's common about dictionaries. This doubles as a dictionary and set review.

|

|

- If you think it will help, pull up the `List` class specification — although this might be better to do after students learn the class syntax.

|

|

|

|

**Talking Points:**

|

|

|

|

- Similarly, you will hear people say that "everything is an object" in Python. Python is an object-oriented programming language.

|

|

- What this means is that nearly every variable you declare actually has a set of properties and methods that it can use — it is an object.

|

|

- Every string, number, list, dictionary, etc. has a set of behaviors and properties that are "baked in" because they are instances of a class.

|

|

- Every list you declare has properties (the values in it) and behaviors — methods like `append()` and `pop()`.

|

|

- In Python, there is a built-in `List` class, which has the ability to hold values, and built-in list methods like `append()` and `pop()`. When you declare a list in Python, you're making your own list object that's a variation of the `List` class.

|

|

</aside>

|

|

|

|

---

|

|

|

|

## Discussion: A `Dog` Class

|

|

|

|

We can make a class for anything! Let's create a `Dog` class.

|

|

|

|

The objects might be `greyhound`, `goldenRetriever`, `corgi`, etc.

|

|

|

|

Think about the `Dog` blueprint. What variables might our class have? What functions?

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

**Pro tip:** When functions are in a class, they are called "methods." A method is a function _within the context_ of a class object.

|

|

|

|

**Pro tip:** While objects are named in snake_case, classes are conventionally named in TitleCase.

|

|

|

|

<aside class="notes">

|

|

|

|

**Teaching Tips:**

|

|

|

|

- Try to lead students toward name, age, color, and barking — that's what will be in the class we create.

|

|

|

|

</aside>

|

|

|

|

|

|

---

|

|

|

|

|

|

## We Do: Defining Classes

|

|

|

|

Follow along! Let's create a new file, `Dog.py`.

|

|

|

|

Class definitions are similar to function definitions, but instead of `def`, we use `class`.

|

|

|

|

Let's declare a class for `Dog`:

|

|

|

|

```python

|

|

class Dog:

|

|

# We'll define the class here.

|

|

# Our dog will have two variables: name and age.

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

**Pro tip:** Files are usually named for their class, so the `Dog` class is in `Dog.py`.

|

|

|

|

<aside class="notes">

|

|

|

|

**Teaching Tips:**

|

|

|

|

- Make sure students do this with you! Practicing syntax is key.

|

|

|

|

**Talking Points:**

|

|

|

|

- It's very common in programming to make our own classes to organize data in the ways we want. Python gives us, for example, a string and an integer.

|

|

- What if we want to store a bunch of data where each item contains a string **and** an integer **and** a function that prints them out nicely?

|

|

- We can make a class for that, and then each object we make from that class will have that all baked in.

|

|

- Note that we can **optionally** (as of Python3) include parentheses after our class declaration, i.e. `class Dog:`

|

|

- All classes, if no explicit inheritance is given, will inherit from the `Object` class (the parent of all Python classes)

|

|

- The base class can be shown by typing `<your_class-name>.__bases__`. If you haven't specified a parent, it should return `object`

|

|

- `class Dog:` is functionally identical to `class Dog:` and `class Dog(object):`.

|

|

</aside>

|

|

|

|

---

|

|

|

|

## We Do: Adding Docstrings, Part 1

|

|

|

|

Using our `Dog` class from the previous exercise, let's add a _docstring_.

|

|

|

|

A [docstring](https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0257/#what-is-a-docstring) is a comment that is placed at the top of a class (or function). When python precompiles the class or function (which happens in the background), it parses this comment and makes it available to the user as a helpfile when the class is accessed when typing the class or function, followed by a `?` question mark. In a Jupyter Notebook, this can also be accessed by placing your cursor at the end of a class or function and pressing `SHIFT + TAB`. Try it out! Enter `list?` in a python interpreter or Jupyter cell and run it. What is returned?

|

|

|

|

```python

|

|

In [1]: list?

|

|

Init signature: list(self, /, *args, **kwargs)

|

|

Docstring:

|

|

list() -> new empty list

|

|

list(iterable) -> new list initialized from iterable's items

|

|

Type: type

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

Here, we can see under the `Docstring` section are the 'instructions for use', and the `Init signature` is a list of arguments that can be passed to the function, which is automatically recognized and generated by the python compiler.

|

|

|

|

|

|

<aside class="notes">

|

|

|

|

**Teaching Tips**:

|

|

|

|

- Give the students a minute to try out getting the docstring on their favorite function or class. Here, we're using a builtin function, but it's also very cool to show the `.__path__` and `.__doc__` private class variables, and where the actual docstring is in a real class like a pandas library.

|

|

|

|

- Direct students to the best practices within [PEP-0257](https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0257/) for creating docstrings. There's a lot to know, more than we have time to cover.

|

|

|

|

- Encourage them to use the PEP syntax reference in the future for other things to make sure their code is standardized and adheres to the [principle of least astonishment](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Principle_of_least_astonishment).

|

|

|

|

</aside>

|

|

|

|

---

|

|

|

|

## We Do: Adding Docstrings, Part 2

|

|

|

|

Using our `Dog` class from the previous exercise, let's add a _docstring_.

|

|

|

|

The docstring for a function or method should summarize its behavior and document its arguments, return value(s), side effects, exceptions raised, and restrictions on when it can be called. Not all of these will be applicable for every function or method, so the programmer should take care to document the parts relevant. Optional arguments should be indicated. It should be documented whether keyword arguments are part of the interface.

|

|

|

|

The first line is a simple description of the class or function, followed by a blank line, followed by keyword arguments, if any.

|

|

|

|

Let's write a docstring for `Dog`:

|

|

|

|

```python

|

|

class Dog:

|

|

"""Creates Dog class, possible child class of Animal

|

|

|

|

Parameters

|

|

----------

|

|

name : str, default blank

|

|

Desired name of Dog

|

|

age : int, default 0

|

|

Age of Dog in years

|

|

"""

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

<aside class="notes">

|

|

|

|

**Teaching Tips:**

|

|

|

|

- Note that we are defining the name and age parameters ahead of time. We haven't created them just yet but we will in the next few steps.

|

|

|

|

**Talking Points:**

|

|

|

|

- Also what is usually included in a class docstring is a 'see also' section, for similar classes, as well as an 'example' section that shows how the class is instantiated and used with some common use cases. This was omitted for brevity.

|

|

- An important part of this docstring is the `type` of the parameter for each parameter. This tells the user how to input data into the class. For example, we _could have_ inserted our age as a string, but we are expecting an int. Since python is not strongly typed, it is important to tell the user of your code what types of variables should be passed.

|

|

- Also important for methods is the `return type` of the method (if any). This will let the user know if they need to 'catch' any object that is returned from the method into a variable.

|

|

|

|

</aside>

|

|

|

|

---

|

|

|

|

## We Do: The `__init__` Method

|

|

|

|

What first? Every class starts with an `__init__` method. It's:

|

|

|

|

* Where we define the class' variables.

|

|

* Short for "initialize."

|

|

* "Every time you make an object from this class, do what's in here."

|

|

|

|

Let's add this:

|

|

|

|

```python

|

|

class Dog:

|

|

"""Creates Dog class, possible child class of Animal

|

|

|

|

Parameters

|

|

----------

|

|

name : str, default blank

|

|

Desired name of Dog

|

|

age : int, default 0

|

|

Age of Dog in years

|

|

"""

|

|

|

|

def __init__(self, name="", age=0):

|

|

# Note the optional parameters and defaults.

|

|

self.name = name # All dogs have a name.

|

|

self.age = age # All dogs have an age.

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

*Note: `self` means "each individual object made from this class." Not every "dog" has the same name!*

|

|

*Note: in the effort of brevity, we wil be omitting the docstring from future examples!*

|

|

|

|

|

|

<aside class="notes">

|

|

|

|

**Teaching Tips:**

|

|

|

|

- `Self` is tough! It will make more sense after you start creating objects. Don't spend more than a few minutes on it — go back to it when comparing instance versus class variables.

|

|

- Call out the default values, or optional parameters, as we very recently learned them.

|

|

- Method means function!

|

|

- Be sure that students are aware that we are omitting the docstring from future examples to keep the code short and concise. They will be expected to have docstrings on classes and methods for their homework! Documentation is critical!

|

|

|

|

**Talking Points:**

|

|

|

|

- When we make an object, we'll first set its variables.

|

|

- The first argument passed to the `__init__` function, `self`, is required when defining methods for classes. The `self` argument is a reference to a future instantiation of the class. In other words, `self` refers to each individual dog.

|

|

- This lets each object made from a class keep references to its own data and function members. Not every "dog" has the same attributes, so we want individual cars to maintain their own attributes.

|

|

- Python allows us to provide default values for parameters in any function we provide. Here, if no `name` or `age` values are provided when a `Dog` is initialized, they will default. To create default values, we assign values to the parameter `capacity` *inside* the parentheses. You've seen this!

|

|

</aside>

|

|

---

|

|

|

|

## We Do: Adding a `bark_hello()` Method

|

|

|

|

All dogs have the behavior `bark`, so let's add that. This is a regular function (method), just inside the class!

|

|

|

|

```python

|

|

class Dog:

|

|

|

|

def __init__(self, name="", age=0):

|

|

# Note the defaults.

|

|

|

|

self.name = name # All dogs have a name.

|

|

self.age = age # All dogs have an age.

|

|

|

|

# All dogs have a bark function.

|

|

"""Prints a message stating name and age to stdout"""

|

|

def bark_hello(self):

|

|

print("Woof! I am called", self.name, "; I am", self.age, "human-years old.")

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

We're done defining the class!

|

|

|

|

*Note: We have also added a docstring to our new `.bark_hello()` method. This will be omitted for future examples for brevity.*

|

|

|

|

<aside class="notes">

|

|

|

|

**Teaching Tips:**

|

|

|

|

- Note that it takes `self`! This will be tough to remember. Point out that it matches how the variable was declared.

|

|

</aside>

|

|

|

|

---

|

|

|

|

## Aside: Instantiating Objects From Classes

|

|

|

|

Now we have a `Dog` template!

|

|

|

|

Each `dog` object we make from this template:

|

|

|

|

* Has a name.

|

|

* Has an age.

|

|

* Can bark.

|

|

|

|

<aside class="notes">

|

|

|

|

**Teaching Tips:**

|

|

|

|

- Point out the lowercase "d!"

|

|

</aside>

|

|

---

|

|

|

|

## We Do: How Do We Make a `Dog` Object?

|

|

|

|

We call our class name like we call a function — passing in arguments, which go to the `init`.

|

|

|

|

Add this under your class (non-indented!):

|

|

|

|

```python

|

|

# Declare the objects.

|

|

gracie = Dog("Gracie", 8)

|

|

spitz = Dog("Spitz", 5)

|

|

buck = Dog("Buck", 3)

|

|

|

|

# Test them out!

|

|

gracie.bark_hello()

|

|

print("This dog's name is", gracie.name)

|

|

print("This dog's age is", gracie.age)

|

|

spitz.bark_hello()

|

|

buck.bark_hello()

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

Try it! Run `Dog.py` like a normal Python file: `python Dog.py`.

|

|

|

|

<aside class="notes">

|

|

|

|

**Teaching Tips:**

|

|

|

|

- Map out that these variables go to `__init__` to get created. All arguments go to `__init__`!

|

|

- They have a working class! Go back through the whole code and make sure students understand.

|

|

- After running this, stop and check for understanding.

|

|

|

|

**Talking Points:**

|

|

|

|

- This will create a new object according to our `Dog` class specification.

|

|

- Python runs our `__init__` method to initialize the object.

|

|

- Here, we are telling our `__init__` method to set the name of this `dog` to `'Gracie'` and set her age to `8` years old.

|

|

- Even though `self` is listed as a parameter for the `bark_hello()` function, we don't pass it into the function. It happens automatically.

|

|

</aside>

|

|

|

|

---

|

|

|

|

## We Do: Adding Print

|

|

|

|

`__init__` is just a method. It creates variables, but we can also add a `print` statement! This will run when we create the object.

|

|

|

|

```python

|

|

class Dog:

|

|

def __init__(self, name="", age=0):

|

|

self.name = name

|

|

self.age = age

|

|

print(name, "created.") # Run when init is finished.

|

|

|

|

def bark_hello(self):

|

|

print("Woof! I am called", self.name, "; I am", self.age, "human-years old.")

|

|

|

|

fox = Dog("Fox") # Note that "Fox created." prints — and we're using the default age.

|

|

fox.bark_hello()

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

Try it!

|

|

|

|

<aside class="notes">

|

|

|

|

**Teaching Tips:**

|

|

|

|

- Run this a few times to show the default variables. Take out the default for name to show that variables don't need a default value.

|

|

|

|

**Talking Points:**

|

|

|

|

- Reminder: "Method" is a function in a class.

|

|

- Note that `print` statements can be anywhere — it's not a variable! `__init__` is a method.

|

|

- The `__init__` method will execute once and only once when you create a new object from a class. Note that the `print` statement never happens again.

|

|

|

|

</aside>

|

|

|

|

|

|

---

|

|

|

|

## Quick Review: Classes

|

|

|

|

A class is a blueprint for an object. Some classes are built into Python, like `List`. We can always make a `list` object.

|

|

|

|

We can make a class for anything!

|

|

|

|

```python

|

|

# Created like a function; TitleCase

|

|

class Dog:

|

|

|

|

# __init__: A method (function) that happens just once, when the object is created.

|

|

def __init__(self, name="", age=0): # What's passed in to the class is used here.

|

|

# Set variables for each.

|

|

self.name = name

|

|

self.age = age

|

|

print(name, "created.") # This will run when the __init__ method is called.

|

|

|

|

# Classes can have as many methods (functions) as you'd like.

|

|

def bark_hello(self):

|

|

print("Woof! I am called", self.name, "; I am", self.age, "human-years old.")

|

|

|

|

fox = Dog("Fox") # Creating the object calls __init__. Objects are snake_case.

|

|

print("This dog's name is", fox.name) # The object now has those variables!

|

|

fox.bark_hello() # The object now has those methods and variables!

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

<aside class="notes">

|

|

|

|

**Teaching Tips:**

|

|

|

|

- Add your own reasons for why classes are useful.

|

|

- Do a quick check for understanding.

|

|

- Run down the comments in the code like they're bullet points!

|

|

|

|

</aside>

|

|

---

|

|

|

|

## Discussion: What About Tea?

|

|

|

|

Let's make a `TeaCup` class.

|

|

|

|

* What variables would a cup of tea have?

|

|

* What methods?

|

|

|

|

<aside class="notes">

|

|

|

|

**Teaching Tips:**

|

|

|

|

- Have the students discuss suggestions for properties for a `Tea` class.

|

|

- The exercise has `capacity`, `amount`, `fill`, `empty`, and `drink`.

|

|

|

|

</aside>

|

|

|

|

---

|

|

|

|

## A Potential `TeaCup` Class

|

|

|

|

We could say:

|

|

|

|

Variables:

|

|

|

|

* A total `capacity`.

|

|

* A current `amount`.

|

|

|

|

Methods:

|

|

|

|

* `fill()` our cup.

|

|

* `empty()` our cup.

|

|

* `drink()` some tea from our cup.

|

|

|

|

<aside class="notes">

|

|

|

|

**Talking Points:**

|

|

|

|

- Given a well-defined cup of tea, we can use the class definition to create **instances** of the class.

|

|

- Each **instance** of the `TeaCup` class can have a different `capacity` and keep track of different `amounts`.

|

|

- Although different, properties are affected by methods like `fill()`, `empty()`, and `drink()` similarly.

|

|

</aside>

|

|

|

|

---

|

|

|

|

## Example: A `TeaCup` Class

|

|

|

|

|

|

Here's what a `TeaCup` class definition might look like in Python:

|

|

|

|

```python

|

|

class TeaCup:

|

|

def __init__(self, capacity):

|

|

# Python executes when a new cup of tea is created.

|

|

self.capacity = capacity # Total ounces the cup holds.

|

|

self.amount = 0 # Current ounces in the cup. All cups start empty!

|

|

|

|

def fill(self):

|

|

self.amount = self.capacity

|

|

|

|

def empty(self):

|

|

self.amount = 0

|

|

|

|

def drink(self, amount_drank):

|

|

self.amount -= amount_drank

|

|

# If it's empty, it stays empty!

|

|

if (self.amount == 0):

|

|

self.amount = 0

|

|

|

|

steves_cup = TeaCup(12) # Maybe a fancy tea latte.

|

|

yis_cup = TeaCup(16) # It's a rough morning!

|

|

brandis_cup = TeaCup(2) # Just a quick sip.

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

<aside class="notes">

|

|

|

|

**Teaching Tips:**

|

|

|

|

- This is the only slide, so just a demo. Talk through each line again to remind students what it does. Copy this to a file and run it!

|

|

- This class doesn't take in `amount`! It's set as a variable, but not passed in. Call it out and explain.

|

|

- Remind students that the object declarations have to go below the class. Show the error that occurs if you try calling `steves_cup` first.

|

|

- Call each function — `fill()`, `drink()` with a different number for each, and printing the amount left with `cup.amount`.

|

|

|

|

</aside>

|

|

|

|

---

|

|

|

|

## Quick Knowledge Check:

|

|

|

|

```python

|

|

class TeaCup:

|

|

def __init__(self, capacity = 8):

|

|

self.capacity = capacity

|

|

self.amount = 0

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

When will the capacity be `8`?

|

|

|

|

<aside class="notes">

|

|

|

|

**Talking Points:**

|

|

|

|

- See if students can answer this.

|

|

- Answer: When no capacity is passed in when it's declared.

|

|

- After giving the answer, demo it!

|

|

|

|

</aside>

|

|

|

|

|

|

---

|

|

|

|

## Variables for All Class Objects

|

|

|

|

Next up: new types of class variables!

|

|

|

|

Let's revisit our `Dog` class:

|

|

|

|

```python

|

|

class Dog:

|

|

|

|

def __init__(self, name="", age=0):

|

|

self.name = name

|

|

self.age = age

|

|

print(name, "created.")

|

|

|

|

def bark_hello(self):

|

|

print("Woof! I am called", self.name, "; I am", self.age, "human-years old")

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

What if there are variables that we want across all dogs?

|

|

|

|

For example, can we count how many `dog` objects we make and track it in the class?

|

|

|

|

<aside class="notes">

|

|

|

|

**Talking Points:**

|

|

|

|

- Our `Dog` class had variables attached to `self` that exist independently for each object that's created.

|

|

* Each object instance has its own copies of these variables, and they can vary across objects.

|

|

- We can attach variables to the class itself so that there's one single thing that exists for an entire class.

|

|

</aside>

|

|

|

|

|

|

---

|

|

|

|

## I Do: Class vs. Instance Members

|

|

|

|

We already have **instance variables**, which are specific to each `dog` object (each has its own name!).

|

|

|

|

A **class variable** is specific to the class, regardless of the object. It's created **above** `__init__`.

|

|

|

|

```python

|

|

class Dog:

|

|

|

|

### Here, we define class variables. ###

|

|

# These are the same for ALL dogs.

|

|

total_dogs = 0

|

|

|

|

def __init__(self, name="", age=0):

|

|

|

|

### These are instance variables. ###

|

|

self.name = name

|

|

self.age = age

|

|

print(name, "created.")

|

|

|

|

def bark_hello(self):

|

|

print("Woof! I am called", self.name, "; I am", self.age, "human-years old")

|

|

print("There are", Dog.total_dogs, "dogs in this room!") # There's no "self" — we call the Dog class name!

|

|

|

|

molly = Dog("Molly", 8)

|

|

molly.bark_hello()

|

|

|

|

sheera = Dog("Sheera", 5)

|

|

sheera.bark_hello()

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

<aside class="notes">

|

|

|

|

**Teaching Tips:**

|

|

|

|

- Demo this, but don't worry about having students follow along. Their understanding is more important than their typing.

|

|

|

|

**Talking Points:**

|

|

|

|

- Our `Dog` class had variables attached to `self` that exist independently for each object that's created.

|

|

* These are called **instance variables**.

|

|

* Each object instance has its own copies of these variables, and they can vary across objects.

|

|

- We can attach variables to the class itself so that there's one single thing that exists for an entire class.

|

|

* These are called **class variables**.

|

|

</aside>

|

|

|

|

---

|

|

|

|

## I Do: Tallying Dogs

|

|

|

|

We can increment the `class` variable any time.

|

|

|

|

```python

|

|

class Dog:

|

|

total_dogs = 0

|

|

def __init__(self, name="", age=0):

|

|

self.name = name

|

|

self.age = age

|

|

Dog.total_dogs += 1 # We can increment this here!

|

|

print(name, "created:")

|

|

|

|

def bark_hello(self):

|

|

print("Woof! I am called", self.name, "; I am", self.age, "human-years old.")

|

|

print("There are", Dog.total_dogs, "dogs in this room!")

|

|

|

|

molly = Dog("Molly", 8)

|

|

molly.bark_hello()

|

|

|

|

sheera = Dog("Sheera", 5)

|

|

sheera.bark_hello()

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

<aside class="notes">

|

|

|

|

**Teaching Tips:**

|

|

|

|

- Again, note that `self` doesn't exist for the `class` variables! Really stress when `self` is there and when it isn't.

|

|

- Show it increasing!

|

|

- Once students get the hang of this, create a method that increments `total_dogs` as well.

|

|

|

|

**Talking Points:**

|

|

|

|

- We can keep a tally of how many `dog`s we have running around in our app.

|

|

- We could put a copy of the tally in each `dog` object, but that's not efficient, as we would be duplicating a value in memory multiple times, and we would have to update the value in every `dog` object in order to keep it accurate.

|

|

- It's much better if we can store it in the class. That way, each `dog` object can access it, but we only need to store it and set it in one place.

|

|

- Finally, we create a new `dog`. The `__init__` method increments the `total_dogs` counter, which is stored in the `Dog` class itself. We can access the value stored in `Dog.total_dogs` inside our script, and each `dog` object can access it from their own functions.

|

|

</aside>

|

|

|

|

---

|

|

|

|

## Partner Exercise: Create a Music Genre Class

|

|

|

|

Pair up! Create a new file, `Band.py`.

|

|

|

|

- Define a class, `Band`, with these instance variables: `"genre"`, `"band_name"`, and `"albums_released"` (defaulting to `0`).

|

|

- Give `Band` a method called `print_stats()`, which prints a string like `"The rock band Queen has 15 albums."`

|

|

- Create a class variable, `number_of_bands`, that tracks the number of bands created.

|

|

|

|

Test your code with calls like:

|

|

|

|

```python

|

|

my_band = ("Queen", 15, "rock")

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

**Bonus:** If the genre provided isn't `"pop"`, `"classical"`, or `"rock"`, print out `"This isn't a genre I know."`

|

|

|

|

<aside class="notes">

|

|

|

|

5-10 MINUTES

|

|

|

|

**Teaching Tips:**

|

|

|

|

- After students do this, create it and talk through it.

|

|

- If you're running short on time, skip an exercise and assign it as homework (the next slide's exercise is more difficult).

|

|

|

|

**Talking Points:**

|

|

|

|

- Imagine that you are working with music data of all different types of genres and want to ultimately define three different classes of music (pop, classical, and rock).

|

|

- Things to think about:

|

|

* Starting values for variables should be set in the `__init__` method.

|

|

* Class variables are declared inside the class but outside any methods.

|

|

* Instance variables are declared inside the `__init__` method.

|

|

* Does your `__init__` method need to accept any parameters?

|

|

</aside>

|

|

|

|

---

|

|

|

|

## Partner Exercise: Create a `BankAccount` Class

|

|

|

|

Switch drivers! Create a new class (and file), `Bank.py`.

|

|

|

|

Bank accounts should:

|

|

|

|

* Be created with the `accountType` property (either `"savings"` or `"checking"`).

|

|

* Keep track of its current `balance`, which always starts at `0`.

|

|

* Have access to `deposit()` and `withdraw()` methods, which take in an integer and update `balance` accordingly.

|

|

* Have a class-level variable tracking the total amount of money in all accounts, adding or subtracting whenever `balance` changes.

|

|

|

|

**Bonus:** Start each account with an additional `overdraftFees` property that begins at `0`. If a call to `withdraw()` ends with the `balance` below `0`, then `overdraftFees` should be incremented by `20`.

|

|

|

|

|

|

<aside class="notes">

|

|

|

|

10 MINUTES

|

|

|

|

**Teaching Tips:**

|

|

|

|

- This is tough! Walk around the room and check for questions and understanding.

|

|

- After students do this, create it and talk through it.

|

|

- If you're running short on time, skip an exercise and assign it as homework.

|

|

|

|

**Talking Points:**

|

|

|

|

- (The same as above.)

|

|

- Things to think about:

|

|

* Starting values for variables should be set in the `__init__` method.

|

|

* Class variables are declared inside the class but outside any methods.

|

|

* Instance variables are declared inside the `__init__` method.

|

|

* Does your `__init__` method need to accept any parameters?

|

|

</aside>

|

|

|

|

---

|

|

|

|

## Knowledge Check: Select the Best Answer

|

|

|

|

Consider the following class definition for `Cat`:

|

|

|

|

```python

|

|

class Cat:

|

|

def __init__(self, name='Lucky'):

|

|

self.name = name

|

|

self.fur = short

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

How would you instantiate a `Cat` object with the `name` attribute `'Furball'`?

|

|

|

|

1. `mycat = Cat(name='Furball')`

|

|

2. `furball = Cat`

|

|

3. `mycat = Cat(self, name='Furball')`

|

|

4. `mycat = Cat.init(name='Furball')`

|

|

|

|

<aside class="notes">

|

|

|

|

**Teaching Tips:**

|

|

|

|

- Have students guess before telling them.

|

|

|

|

**Answer:**

|

|

|

|

1. The `__init__` function is automatically called when creating an object with the `Cat(name='Furball')` syntax.

|

|

</aside>

|

|

|

|

---

|

|

|

|

## Knowledge Check: Select All That Apply.

|

|

|

|

Which of the following statements are true about the ```self``` argument in class definitions?

|

|

|

|

- The user does not need to supply `self` when using instance methods.

|

|

- The `self` argument is a reference to the instance object.

|

|

- Any variable assigned with `self` (e.g., `self.var`) will be shared across instances of the class.

|

|

- With an instance object, `obj`, entering `obj.self.var` will provide the value for `var` for that instance.

|

|

|

|

<aside class="notes">

|

|

|

|

**Teaching Tips:**

|

|

|

|

- Have students guess before telling them.

|

|

|

|

**Answers:**

|

|

|

|

1. The user does not need to supply `self` when using instance methods.

|

|

2. The `self` argument is a reference to the instance object.

|

|

|

|

Correct response explanation:

|

|

|

|

- `self` is automatically passed into an instance method when you call it. `self` refers to the class and NOT the instance. `self.var` will not be shared between instances, as `self` refers to the class. Instances have no explicit `self` attribute.

|

|

</aside>

|

|

|

|

---

|

|

|

|

## Knowledge Check: Select the Best Answer

|

|

|

|

|

|

Consider the following code:

|

|

|

|

```python

|

|

class Shape(object):

|

|

possible = ['triangle','square','circle','pentagon','polygon','rectangle']

|

|

|

|

def __init__(self, label='triangle'):

|

|

self.label = label

|

|

|

|

def is_possible(self):

|

|

if self.label in self.possible:

|

|

print('This is possible')

|

|

else:

|

|

print('This is impossible')

|

|

|

|

square = Shape(label='square')

|

|

wormhole = Shape(label='wormhole')

|

|

square.possible.append('wormhole')

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

If you were to enter `wormhole.is_possible()`, would the outcome be `"This is possible"` or `"This is impossible"`?

|

|

|

|

<aside class="notes">

|

|

|

|

**Teaching Tips:**

|

|

|

|

- Have students guess before telling them.

|

|

|

|

**Answer:**

|

|

`This is possible`

|

|

|

|

Correct answer explanation:

|

|

|

|

- The possible list is defined at the class level as opposed to as an instance variable. When we append the string `'wormhole'` to the possible list of the `square` object, this list is shared with the wormhole instance. Therefore the output will be `This is possible`.

|

|

</aside>

|

|

|

|

---

|

|

|

|

## Summary: Discussion

|

|

|

|

Let's chat! Can anyone explain:

|

|

|

|

- What a class is?

|

|

- What `__init__` does?

|

|

- What an object is?

|

|

- The point of `self`?

|

|

- The two types of variables?

|

|

|

|

|

|

<aside class="notes">

|

|

|

|

**Teaching Tips:**

|

|

|

|

- Go through each question and make sure students can explain the answers. Check for understanding!

|

|

</aside>

|

|

|

|

|

|

---

|

|

|

|

## Summary and Q&A

|

|

|

|

Class:

|

|

|

|

* A pre-defined structure that contains attributes and behaviors grouped together.

|

|

* The blueprint.

|

|

* Defined via a method call.

|

|

* Contains an `__init__` method that takes in parameters to be assigned to an object.

|

|

* E.g., the `Dog` class; the `List` class.

|

|

|

|

Object:

|

|

|

|

* An instance of a class structure.

|

|

* The items built from the blueprint.

|

|

* E.g., the `gracie` object; the `my_list` object.

|

|

|

|

---

|

|

|

|

## Summary: Types of Variables in a Class

|

|

|

|

Instance variables:

|

|

|

|

- Contain data types declared in the class but defined in each object.

|

|

- Each `dog` has its own name and age.

|

|

- Each `my_list` has its own elements.

|

|

|

|

Class variables:

|

|

|

|

- Contain data and methods that span across all objects.

|

|

- How many `dog` objects are there in total?

|

|

- The `self` keyword lets us distinguish between variables that exist at the class level versus in each object.

|